Over many centuries, people living the Northern hemisphere have the coming of Spring. No one can be sure when the seasonal tradition of ‘May Day’ or Beltane began. What we do know about spring festivals is how diverse they were across huge areas of land, culture, climate, and physical landscape. Accounts have been recorded from Ireland to Russia, as far south as France, and as far north as Scandinavia. There are thousands of expressions of the celebration of Spring through May Day, each simultaneously similar and unique.

For many, it is precisely the magical mystery of May Day’s ‘true’ origin that provides its appeal and encourages creativity. We do know that this ritual is ancient, and as you will see, we have the ability to participate in its timelessness.

For many, it is precisely the magical mystery of May Day’s ‘true’ origin that provides its appeal and encourages creativity. We do know that this ritual is ancient, and as you will see, we have the ability to participate in its timelessness.

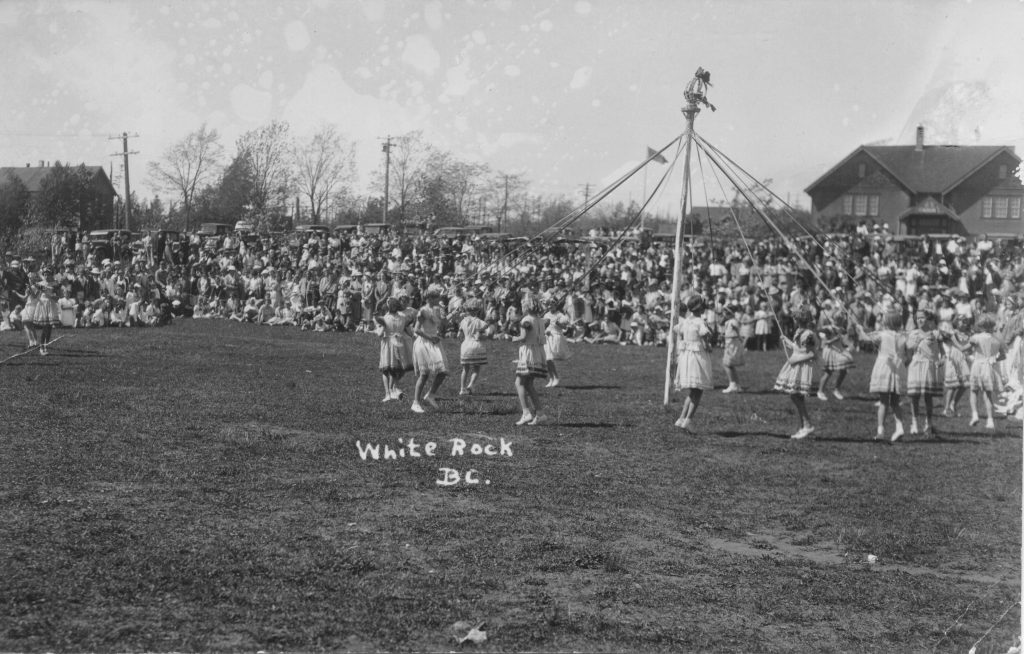

Our current exhibition explores the use of costume and performance at May Day and how it shaped cultural identity in early White Rock. It also showcases contemporary spring festivals of May Day and Beltane in the Lower Mainland.

The Role of Costume in Spring Festivals

The combination of public festivals and costumes is a powerful means to communicate community identity, values, and character. Each of us has been a part of a ceremony or occasion where a costume, or a particular kind of regalia or clothing, is socially appropriate and even expected of us. Anthropologist Marshall Sahlins argued that costumes and regalia are as informative as our use of language to convey meaning, membership in a community or group, and social values.

Costumes featured heavily in White Rock’s May Day celebrations that took place from 1923-37, 1940-41, and 1946-49. In addition to the May Queen suite, and the men and flower girls on stage, many other costumes were worn as part of May Day festivities. What do these costumes convey to you? Take note of the difference in costumes worn according to gender: little girls in white, men wearing darker clothes.

May Day in White Rock

White Rock held its first May Day celebration in 1923. It was designed almost identically to festivities that had been taking place in New Westminster for nearly 50 years. White Rock and New Westminster even shared the same emcee for several years, ‘Mr. May Day’, JJ Johnston. The May Queen and her royal party attended New Westminster’s May Day as honoured guests.

White Rock held its first May Day celebration in 1923. It was designed almost identically to festivities that had been taking place in New Westminster for nearly 50 years. White Rock and New Westminster even shared the same emcee for several years, ‘Mr. May Day’, JJ Johnston. The May Queen and her royal party attended New Westminster’s May Day as honoured guests.

In general the flow of May Day in White Rock involved a parade, a ceremony to crown the May Queen and her Royal Party, Maypole dancing and music, games for all children, and sweet treats. In the evening, the community was invited to a banquet with dinner and dancing. Each celebration began with a costume-filled parade that ended at the White Rock Elementary School grounds. Children who were not part of the Royal Party dressed up in other festive costumes. For example, some young people would wear their Scout or Guide uniform, and some families even decorated their cars.

White Rock’s May Day Connection to New Westminster

New Westminster had its first May Day in 1870, a time when the British colony of British Columbia was in its infancy. The first May Day was held to foster community spirit and was meant for the whole family. It was a day of food and games for everyone. Many adults had likely participated in May Day celebrations as children in Britain. By enacting their collective memories in New Westminster, settlers demonstrated their common British settler identity and created new British traditions of May Day in BC. New Westminster’s May Day became a model that many towns across BC mimicked.

May Day celebrations in BC performed cultural links to the British Empire. ‘May Day’ was synonymous with ‘Empire Day’ in the 1930s and 1940s across the province. Today, communities in BC that still celebrate a British-style May Day hold it around the occasion of Queen Victoria’s birthday, May 24, as did White Rock during its time.

Contradictory Colonialism

While British immigrants and their children dressed up, danced, and sang songs on indigenous land First Nations people were forcibly prevented from holding their own cultural celebrations. In 1876, the Canadian government established the Indian Act. In various ways, the Indian Act prevented First Nations people from expressing their own culture and language through celebration and festival.

In 1884, one of the most significant indigenous events officially banned in BC was the potlatch. Potlatch ceremonies, depending upon the culture, celebrate many things. They involve singing, dancing, and costume. Section 3 of An Act Further to Amend The Indian Act, 1880 reads:

“Every Indian or other person who engages in or assists in celebrating the Indian festival known as the ‘Potlatch’ or in the Indian dance known as the ‘Tamanawas’ is guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall be liable to imprisonment … and any Indian or other person who encourages … an Indian or Indians to get up such a festival or dance, or to celebrate the same, … is guilty of a like offense.”

While potlatches today are no longer banned by the Canadian government, the Indian Act persists in 2019. Today, First Nations communities continue potlatch traditions and are resiliently carrying them into the future.

May Day Ends in White Rock

Public schools played a significant role in facilitating children’s participation in May Day. In White Rock, May Day was held on school grounds; teachers and parents planned and carried out the event, and cancelled school to celebrate. By 1949, the celebration lost momentum, and it was the final year for May Day in White Rock. However, communities in Surrey continued May Day into the late 1970s. New Westminster never stopped.

Beltane: A Contemporary Spring Celebration

Beltane celebrations are a relatively recent phenomenon in North America, and became more popular in the 1960s and ‘70s. Beltane has been celebrated by a small community of people in the Fraser Valley since 1976.

This community made conscious choices about the lineage of their Beltane festival, and celebrate around May 1. They draw on seasonal celebrations with roots in ancient Western traditions, far earlier than the British Empire of 150 years ago. Their celebrations are opposed to modern commercialism that is associated with most seasonal holidays.

This Beltane celebration integrates several seasonal traditions from across Western Europe, and enjoys the diversity of ways to celebrate. The main point of this celebration is to commune with the magical and spiritual forces of Nature, and encourage her to bring warmer weather, flowers, and sunshine after a long dark winter season. Like earlier settler-style May Days, there is a series of events throughout the day at Beltane. These include Maypole dancing, live music, games, a bonfire, and a feast. One of the most unique features of this particular Beltane festival is The Quest play.

The Significance of the May Pole

The first written evidence of a Maypole is from the mid-1300s by Gryffydd ap Adda ap Dafydd. We know that in Welsh and English speaking areas of Europe the Maypole was well established by 1400. Accounts of Maypoles are also found in France, Sweden, and Russia. Queen Victoria was a supporter – and even a reviver – of May Day traditions, and she encouraged the use of Maypole dancing. Her encouragement came as part of a larger cultural shift in the late 1800s when people had begun remembering ‘simpler times’ before the industrial revolution. Victorian May Day celebrations were a way to experience days gone by, and to connect with cultural roots. Dancing around the Maypole is generally understood to signify the happy season of warmth, and to celebrate the return of green vegetation. This is an event that the community can gather around.

Head to the Museum gallery to try out our May pole!